Writing Criteria, Part Three: Organization Modes

SaveIf readers say your writing seems disorganized, it's probably not following the right mode for the job.

By Patricia Roy

Whether you are in the planning stages or revising a draft, understanding organization modes ensures your details follow a logical order. Organization modes are the principles by which you arrange the details in your writing. If readers say your writing seems disorganized, it's probably not following the right mode for the job.

It should be noted that I haven't described all the modes here. I'd rather give you the big three (or four, if you consider compare/contrast separately) since most assignments are a version of these.

The Modes

Time Segments or Narration

When you organize by time segments, your subject reads like a story. The paragraphs move through time, usually starting with time markers, such as "once upon a time," "first," "second," "third," "next," "after," or "lastly."

This arrangement does not have to follow chronological order although that is probably the most common. Lots of stories use time loops or flashbacks. In those cases, the jumps in time help create suspense, which is enjoyable for something like a science fiction film or a mystery series. However, gaps in the timeline confuse readers when they just want to follow recipe directions or use a new software tool.

In addition to directions, time segments work well for personal narratives, memoirs, procedures, or cause-and-effect relationships. Anytime there are steps leading to an outcome, this mode works.

Parts of a Whole or Description

When you organize by parts of a whole, it's like taking a photograph. You are capturing all the static details of a thing. In contrast with time segments, parts of a whole does not use time markers because the focus isn't changing over time. Instead, words denoting spatial relationships might be used, such "in the foreground," "behind," "in the sidebar," or "on the second floor."

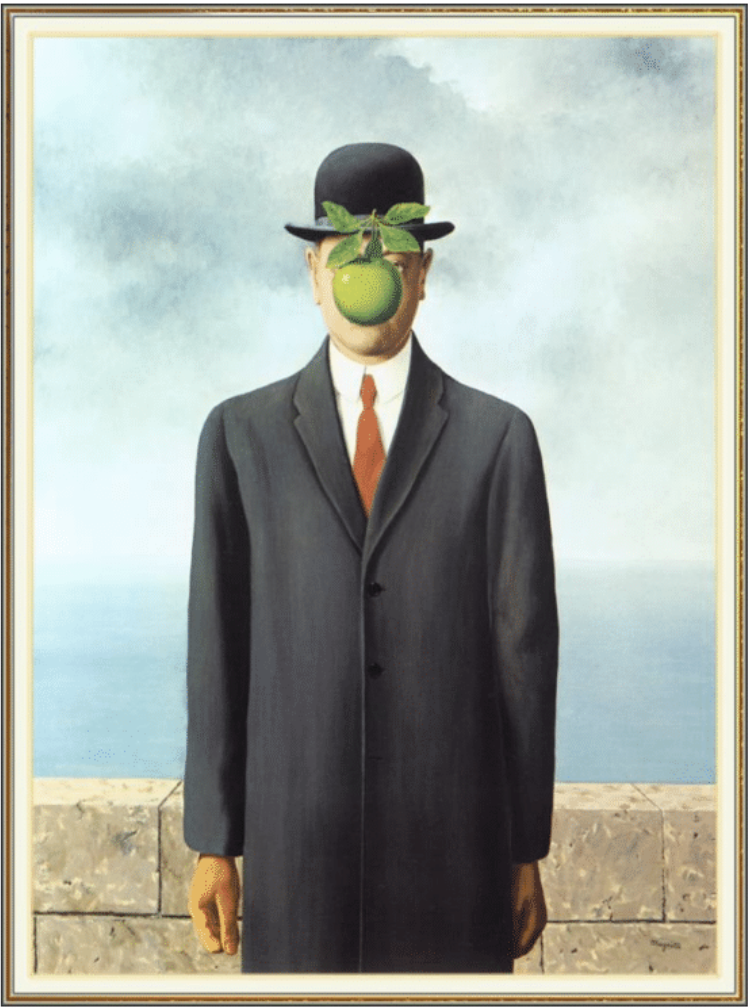

Students sometimes struggle with this one if they have not discovered a clear relationship between the parts. Think about how you might describe a painting. Where would you start? Most paintings focus on a subject, let's say a man in a funny hat. Start there, then move onto what is closest to the man, and then what is next to that, etc. You could also move from left to right (the reading direction for most Western languages) or from the foreground to the background or vice versa. Whatever you choose, describing the parts in a logical order gives the reader who has not seen the painting a mental picture of it (see a description of the painting below here).

[Rene Magritte, Son of Man, 1964]

This is a good mode for describing physical things using sensory details. It's very good for observations or field notes in all the sciences, including the social sciences. Even so, poets are often scholars of description. To read a classic example of the power of observation and description, read "Look at Your Fish" by Samuel Scudder. I guarantee you will never look at a fish the same way again.

Classification

Classification is the big Kahuna of the modes, especially for academic writers. It's a large, catch-all term for several similar modes, including analogy, criteria, problem/solution, and compare/contrast. When classifying the details in your writing, you are grouping them according to categories. It's similar to parts of a whole, but more analytical of the relationships between those parts. For example, in order to analyze or classify the painting above, I first need to be able to describe it. I can't analyze why the man's face is covered by an apple until I describe that feature.

Think of classification like artistic movements or movie genres. For example, Star Wars fits solidly into the science fiction genre. How do you know? The distinguishing features of Star Wars are consistent with other movies in that genre: they are futuristic, involve space travel, feature alien beings, use advanced technology, or depict adventure. These features act as a criteria or checklist.

Classifying involves analysis, so any time your teacher asks you to analyze, define, argue, or explain a topic in writing, this mode might be useful.

Compare/Contrast

In this sub-category of classification mode, the writer is classifying the details of two or more items. Those items must have something to compare, something in common. However, the significance comes from the distinctions or contrasts. For example, you might compare and contrast two different versions of the same movie, made in different times by different directors. Or, you might compare and contrast works from the same director.

It's important for compare/contrast papers to have a clear focus and a reason to be comparing the items. It is not enough to just list all the details about each item. What's the point? Is one movie better than the other? Why? How you organize the points of comparison becomes critical to the overall point you are trying to make.

When you organize a compare/contrast essay, you have two choices: organize by items or by points of significance. For example, let's say you are comparing two productions of Romeo and Juliet, the Franco Zeffirelli version (1968) and the Baz Luhrmann remake (1996).

Based upon the same play by Shakespeare, they share many of the same plot points, characters, themes, and language. However, anyone who has seen both films knows that the settings are remarkably different.

Organizing by item, you will discuss all the relevant details from one film first before moving onto the next, making sure to address the points of significance of each item in the same order. That means if you discuss the masquerade ball first in the Zeffirelli version, when you get to Luhrmann, you start with the masquerade as well. That's where you get both the comparison (it's the same scene) as well as the contrast (you can point out what is significant about the differences).

Your other choice is to organize by points of significance. In this case, you would go back and forth between the two items following a list of points. You might start with a sentence like, "Both the Zeffirelli and Luhrmann versions present the chance meeting of the two lovers as unexpected and innocent." Then, you would write about Zeffirelli's masquerade, followed immediately by a section about Luhrmann's depiction of the party. And so on throughout the paper.

Your Organization Mode: Strictly on a Need-to-Flow Basis

To determine what mode a draft employs, find its focus or thesis and all the topic sentences or main points (include titles and subtitles if your draft uses those—they are definitely part of the organization). If you just read those sentences, it should be like reading an outline or mini version of the paper. If the paper is well-organized, it should resemble one of the modes given here.

If not, ask yourself what is the prevailing mode and determine if some of the topic sentences and subsequent paragraphs can be rearranged or rewritten to bring the paper into alignment. Don't be afraid to cut paragraphs that don't flow with the rest. You can always rewrite details to suit the organization, and if not, do you really need those details? Understanding the mode can suggest new areas for development, so even if you need to do some rewriting, the paper will be better for it.

Patricia Roy

Patricia Roy is a writer and professor who has helped students succeed for over 25 years. She started her career as a high school English teacher and then moved into higher education at Tuition Rewards member school, Lasell University in Newton, Massachusetts. Her practical guidance and enthusiasm motivate and inspire students to fearlessly explore their own passions. Professor Roy is also a freelance writer and published poet.Articles & Advice

Featured Articles from The SAGE Scholars Benefit

Tips For Creating A College Admission Video Portfolio

What is the TEAS Test?